Has the balance of power between China and Taiwan shifted decisively? Does this explain the newfound interest of the Biden administration in clarifying its Taiwan policy?

The purpose of making a deterrent threat is to prevent war. Asserting that the United States would come to the defense of Taiwan is intended to dissuade China from an invasion. Historically, the purpose of ambiguity was to deter both Beijing and Taipei, the former from an invasion and the latter from a declaration of independence that would amount to a virtual declaration of war.

This delicate balance has held for nearly forty years, but it shouldn’t be thought of as a policy frozen in amber.

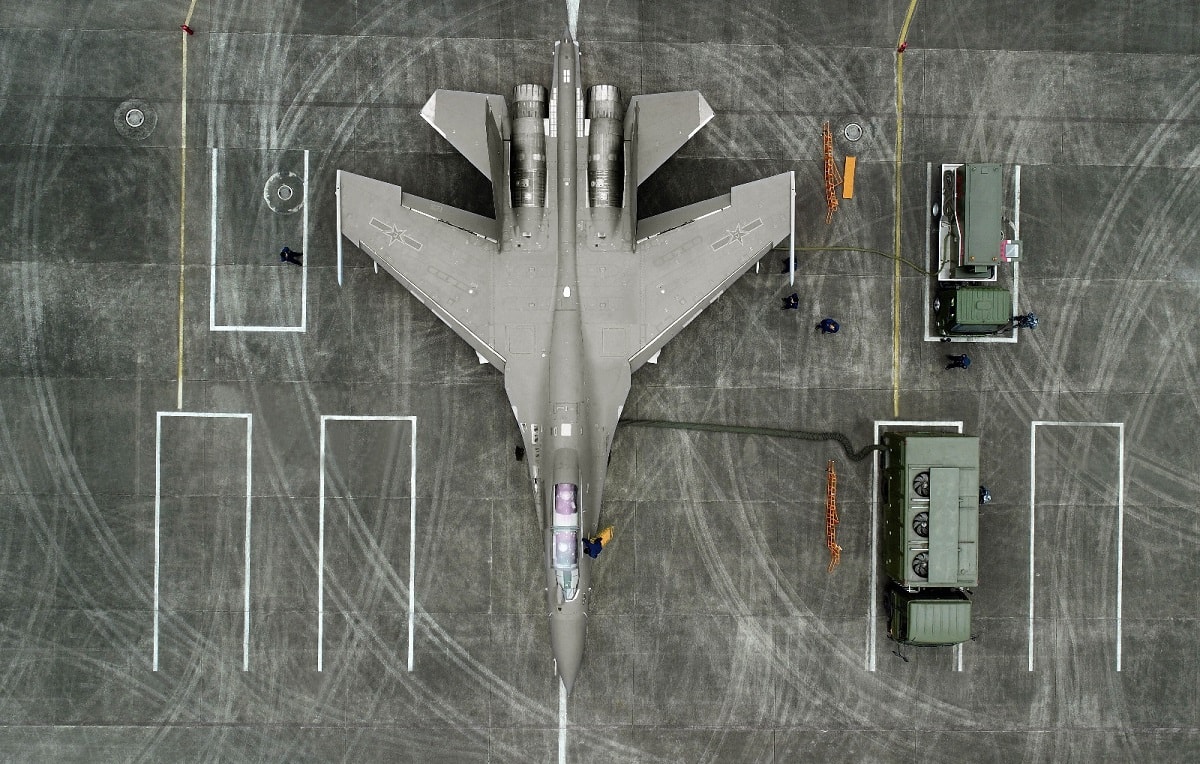

Adding to either side of the scale can upset the balance and call for a new approach to policy. And there is no doubt that at least one element is rapidly changing; Beijing has significantly increased its military capabilities over the last decade, to the extent that a re-evaluation of the balance is now necessary.

Other elements are also changing, as relations between Washington and Beijing have taken a decided turn for the frosty, and the experience of the Russia-Ukraine War gives us a better sense of what a 21st-century military confrontation might look like. Indeed, the debate over the balance of military power across the Taiwan Straits has escaped the analytical community and is now firmly in the wild. A wargame conducted by the Center for New American Security was recently featured on NBC’s Meet the Press, making the tools and techniques of wargame analysis available to a much broader audience.

There are some things we have known for a while. Invading Taiwan would be an intensely difficult operation, no matter how well-capitalized the Chinese military is. The invasion of Normandy in June 1944 required not just months of intense preparation (preparation that would be obvious to modern surveillance technology), but also the development of nearly two years of knowledge about amphibious assault practice. This “know how” was developed in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, but required bloody attacks against well-defended French, Italian, and Japanese positions.

The Chinese have none of this; they must make do with effective, realistic wargaming. The CNAS wargame emphasized the importance of airpower and especially the integration of sea and airpower. The ability to hold Chinese ships at risk during the dangerous crossing made it difficult for China to achieve a foothold and, perhaps more importantly, to keep that foothold reinforced and resupplied. Again, this is a thing we have known, but the wargame serves to reinforce and confirm our impressions.

But there are some things that we don’t know, and there are some lessons that analysts are trying to derive from the Russia-Ukraine War. The operational situation is vastly different, but that does not mean it’s impossible to learn from the experience of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. For one, the invasion has demonstrated that it is simply no longer possible to achieve strategic or even operational surprise. In 1944 the Allies had the latter if not the former, which allowed them to concentrate their forces while the Germans spread theirs thin. The Chinese will not have such an advantage, as their military maneuvers will be glaringly obvious even to open-source analysts.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict also demonstrated that air superiority is difficult to achieve, even for a force that has significant quantitative and qualitative advantages. Ukraine’s ability to continue to operate aircraft even at a numerical disadvantage will surely influence how Taiwan thinks about its own force employment. In a conflict isolated to Taiwan and China, China would undoubtedly enjoy the advantage of numbers and would also have some technological advantages. Taiwan would offset these advantages by taking advantage of distance (its aircraft operate from closer airbases), and a more favorable defensive situation (Taiwan’s air defense network would begin the war intact, and would exact a dreadful toll on the Chinese).

With respect to both of these Ukraine, experience holds some lessons; Russian SEAD has been disappointing, and while the Chinese will probably derive greater attention to the suppression of Taiwanese air defenses in their own campaign, they lack the decades of experience that the United States has developed in this task. Like the Russians, the Chinese may find that it is too dangerous to regularly use their aircraft in close proximity to Taiwan.

China can threaten US vessels and Taiwanese land installations with a vast armada of ballistic and cruise missiles, including land-based, sea-launched, and air-launched weapons. Russia has used such munitions extensively against Ukraine, although to less decisive effect than many expected. While we might expect that Chinese missiles will perform better than Russian missiles (estimated at a 60% failure rate), we don’t actually have any concrete information to support that conclusion; Russian systems have been tested in battle in Syria, Georgia, and Ukraine in a way that the Chinese cannot match. The Ukrainians have taken advantage of their strategic depth in order to repair and rehabilitate damaged facilities, reducing or eliminating the advantages that the Russians could expect to earn from long-range fires. Moreover, the Russians have not been able to target mobile forces in the Ukrainian rear with any degree of effectiveness. It is not obvious that the Chinese will be able to do any better.

Thus, there are many factors worth wargaming. At the same time, we must keep in mind that wargames have a political purpose. In the United States, the services (or the defense industrial base) can take the results of a wargame to Congress in order to demonstrate the need for additional funding or for an additional weapon system. In the case of the CNAS wargame, the purpose is to inform a broad audience of fundamental changes in military capabilities. But wargames do two other things; they help us to understand the nature of a situation, and they show us ways to improve our prospects. The Chinese military is undoubtedly doing its own wargaming work, evaluating the prospects for an attack on Taiwan and honing its capabilities for undertaking such an attack. Which side makes the right assumptions and learns the correct lessons could very well have a decisive impact.

Now a 1945 Contributing Editor, Dr. Robert Farley is a Senior Lecturer at the Patterson School at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Farley is the author of Grounded: The Case for Abolishing the United States Air Force (University Press of Kentucky, 2014), the Battleship Book (Wildside, 2016), and Patents for Power: Intellectual Property Law and the Diffusion of Military Technology (University of Chicago, 2020).