Summary and Key Points: Napoleon understood that even the best campaigns can unravel under the fog of war—bad weather, shaky logistics, human error, and sudden panic can flip outcomes fast.

-His edge wasn’t just battlefield brilliance, but resiliency: absorbing setbacks, regrouping, and re-concentrating force to regain momentum.

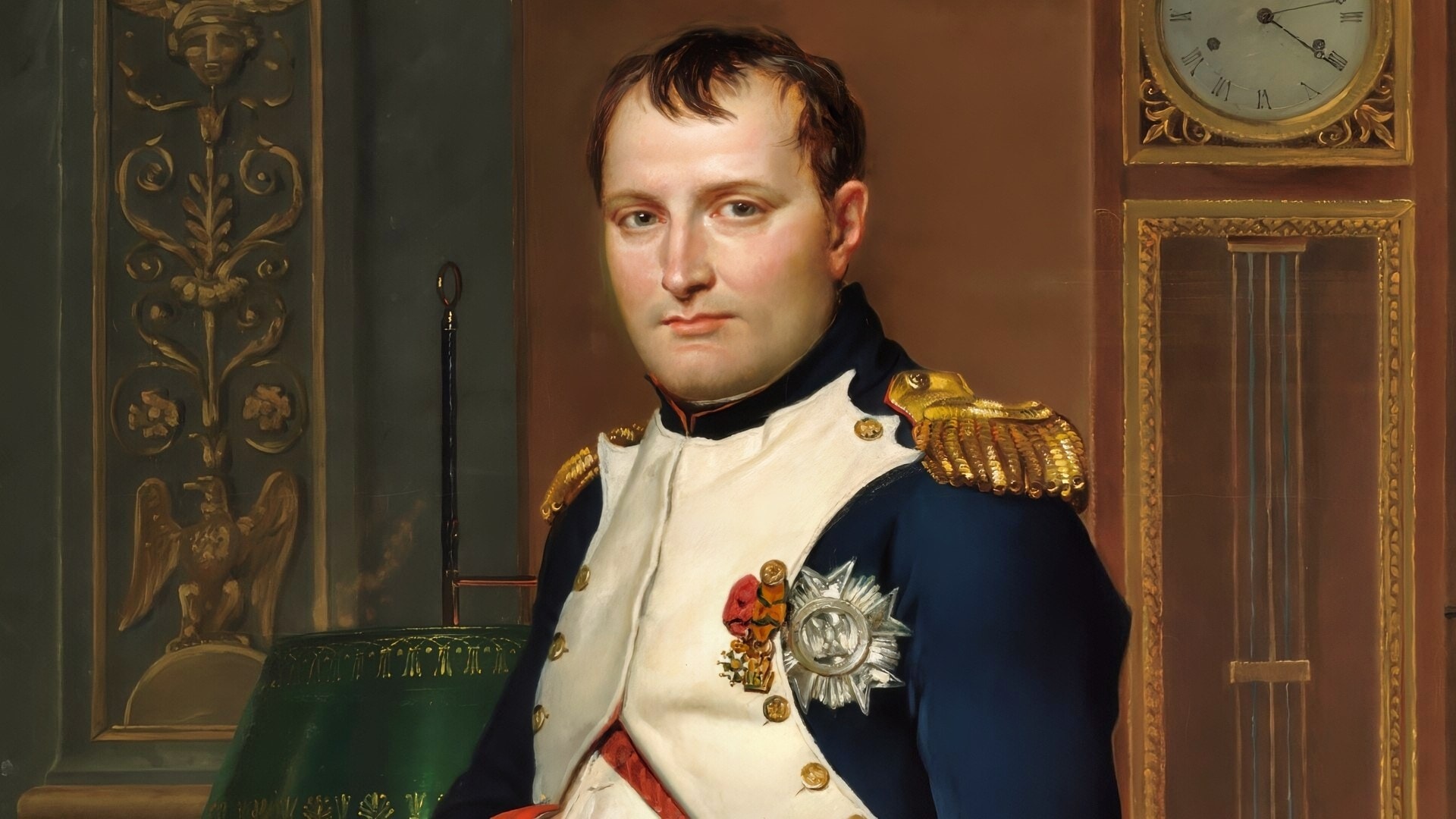

Napoleon Painting Creative Commons Image

-At Marengo in 1800, French forces reeled under Austrian pressure until a rapid reorganization and a decisive counterpunch—helped by General Louis Desaix—turned the fight.

-Leipzig in 1813 was different: outnumbered and battered, Napoleon’s retreat collapsed, accelerating his downfall. Yet even exile didn’t end him—he returned from Elba for one last attempt.

Napoleon’s “Secret Weapon” Wasn’t Genius—It Was How He Recovered After Defeat

“Victory is not always winning the battle…but rising every time you fall.” – Napoleon Bonaparte

You can’t win them all. One might think a general as successful as Napoleon could never even conceive of a battlefield defeat. He was full of military victories and full of himself. But winning every battle is not possible, even for a military genius. There were times to lick wounds and come back even stronger.

The ‘Fog of War’ Did Not Blind Bonaparte

Napoleon realized the fog of war could lead even the best-planned campaign to disaster. His generals could make mistakes. Logistics could fail. Scared soldiers could beat a hasty retreat. The weather could bog down advances. These unpredictable realities of warfare could take down even the best armies.

Napoleon Painting. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Bonaparte Could Take a Beating and Still Recover

Bonaparte was always looking for the decisive victory that would break the enemy’s will to fight. But armies need resiliency. The best military forces might react better to a defeat than a win. Losing shocks the senses. An army can take the lessons learned from a bad performance and adjust the next battleplan. Death is often the driver of military innovation. Like a boxer, soldiers must be able to take a punch and not panic. Setbacks create intellectual and physical growth in a fighting force. The survivors know that casualties are inevitable—to keep the number of dead and wounded to a minimum after a defeat requires grit and perseverance.

An army cannot lose its passion and enthusiasm after a loss. That results in the loss of speed and momentum, a bigger disaster than any single defeat. Bonaparte was expert in inspiring his troops to remain on the comeback trail after a defeat.

Turning Adversity Into Victory

In his early career, Napoleon could snatch victory from the jaws of defeat by re-concentrating his remaining forces and surprising the enemy with their newfound determination. Napoleon never wavered during setbacks. His example showed officers under his command that ultimate victory would come from even the most adverse circumstances.

Battle of Marengo

At the Battle of Marengo in June 1800, the Austrians had the upper hand.

They stung Napoleon’s forces in a storm of cavalry and infantry that surprised the French leader. French forces scattered, and Napoleon had to act quickly or lose outright. The French began an orderly retreat and bought valuable time. Despite being outnumbered, Napoleon regrouped and led a counterattack.

Napoleon ordered General Louis Desaix to make a stand. Desaix did not disappoint; he turned his forces back to the battle and spurred his men forward. This time, it was the Austrians who were surprised. Napoleon poured more troops into the breakthrough of the Austrian lines—Desaix had saved the day.

Napoleon the Emperor. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Napoleon allowed his subordinates to make timely decisions on the battlefield and to figure out their own tactics without micro-managing their activity. Desaix’s advance led to his cavalry forces riding into the breach, creating a winning spearhead. More infantry filed in and pushed the Austrians back. Napoleon had his comeback victory.

Battle Of Leipzig

The Battle of Leipzig in 1813 was a terrible defeat for Napoleon. French troops numbered about 185,000. They faced a strong force of 320,000 allied troops, including Austrian, Prussian, Russian, and Swedish forces.

Napoleon had earlier failed to take Berlin and had concentrated his forces around Leipzig. The preceding Berlin campaign was a disappointment for Napoleon, and even though he was outmatched by allied forces in Leipzig, he sought to make another comeback. But the allies were just too tough to handle this time.

“The allied attack on the 18th, with more than 300,000 men, converged on the Leipzig perimeter. After nine hours of assaults, the French were pushed back into the city’s suburbs. At 2 am on October 19, Napoleon began the retreat westward over the single bridge across the Elster River.

All went well until a frightened corporal blew up the bridge at 1 pm, while it was still crowded with retreating French troops and in no danger of allied attack. The demolition left 30,000 rear guard and injured French troops trapped in Leipzig, to be taken prisoner the next day.

The French also lost 38,000 men killed and wounded,” according to Encyclopedia Britannica.

On the Comeback Trail from Banishment

Napoleon then had to retreat to France. The allied coalition had a chance to strike decisively, as they sensed Napoleon panicking for the first time in his career. The allies streamed into France and took Paris. As a result, Napoleon was banished to the Mediterranean island of Elba.

That was not the end of Bonaparte, though. He made the biggest comeback of his career by escaping Elba and returning to France. French troops decided to switch back to their beloved leader during a period called the One Hundred Days.

While Napoleon later faced the ultimate defeat of his career, at Waterloo, he knew how to make a military and political comeback, even after dreadful conditions and a loss of confidence from his disastrous invasion of Russia. He may have pushed his army beyond their capabilities, but he recognized that sometimes battlefield defeat could create an opportunity for a strong response and an eventual victory.

About the Author: Brent M. Eastwood

Author of now over 3,000 articles on defense issues, Brent M. Eastwood, PhD is the author of Don’t Turn Your Back On the World: a Conservative Foreign Policy and Humans, Machines, and Data: Future Trends in Warfare plus two other books. Brent was the founder and CEO of a tech firm that predicted world events using artificial intelligence. He served as a legislative fellow for US Senator Tim Scott and advised the senator on defense and foreign policy issues. He has taught at American University, George Washington University, and George Mason University. Brent is a former US Army Infantry officer. He can be followed on X @BMEastwood.