Eighty years ago the Imperial Japanese Navy pulled off an astonishing feat of arms, pummeling the U.S. Navy battle line moored at Pearl Harbor.

The operation was an abject failure.

Am I contradicting myself? Not at all. The Japanese Kidō Butai, or aircraft-carrier striking force, had crossed thousands of miles of storm-tossed seas to draw within reach of O’ahu, home to the U.S. Pacific Fleet—the major obstacle to the Japanese militarist regime’s schemes of conquest in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific. Admiral Chūichi Nagumo’s fleet was made up of six fleet carriers, a combined air wing numbering 450 combat aircraft of all types, and a retinue of battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and auxiliaries to provide the flattops with protection, supplies, and support.

Surging such a force from Japanese home waters to Hawai’i was a monumental task. The fleet stretched its logistical tether to the breaking point, and then some. But it succeeded anyway in a tactical sense. Two waves of fighters, torpedo planes and dive bombers swooped in on their targets on the morning of December 7, 1941, a date President Franklin Roosevelt prophesied would “live in infamy.” Ninety-four U.S. Navy men-of-war lay at Pearl Harbor that day, but the priority targets for Japan were the eight battleships moored in pairs at Ford Island, in the middle of the harbor.

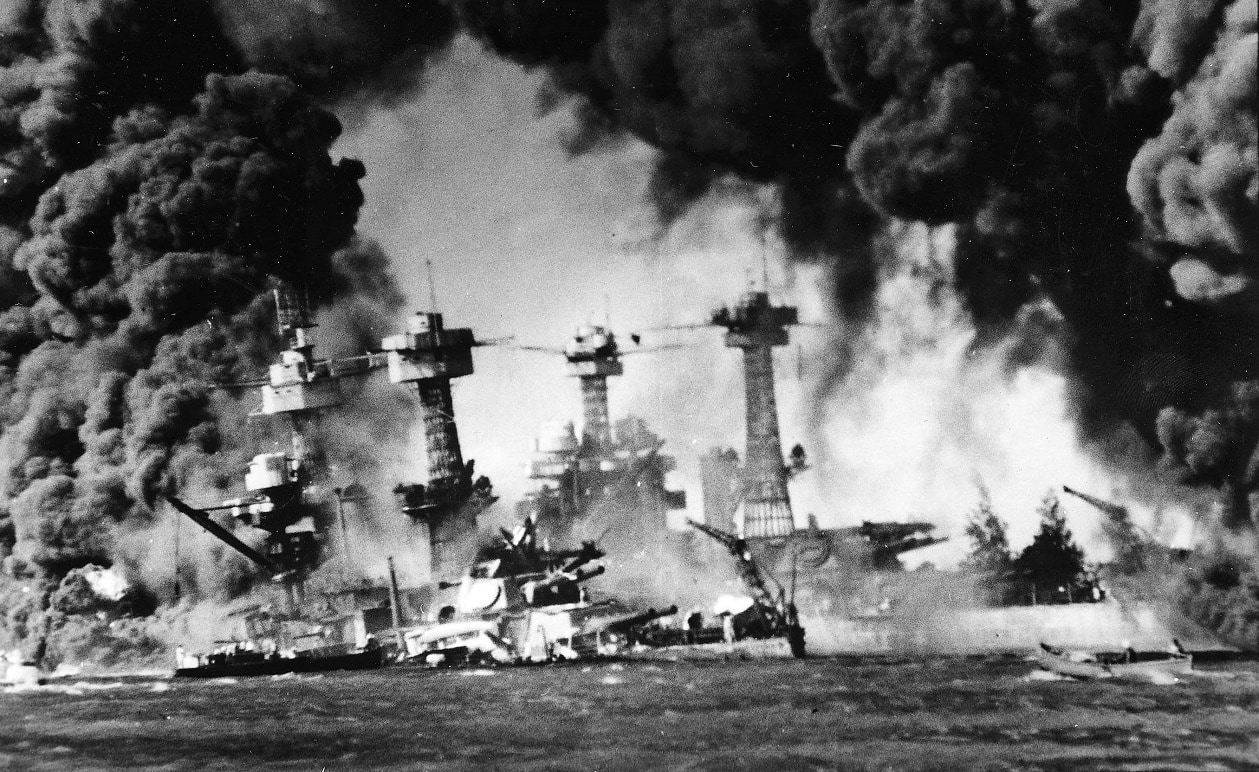

Here’s how Samuel Eliot Morison, the Harvard historian and great chronicler of naval operations in World War II, tells it: “Half an hour after the battle opened, Arizona was a burning wreck, Oklahoma had capsized, West Virginia had sunk, California was going down, and every other battleship (except Pennsylvania in drydock) had been badly damaged.” (Thankfully Pacific Fleet aircraft carriers were at sea on December 7, ferrying aircraft to airfields elsewhere in the Pacific.)

By 8:25 that morning the first wave of attacks on Pearl Harbor was complete. By then, Morison attests, “the Japanese had accomplished about 90 percent of their objective—they had wrecked the Battle Force of the Pacific Fleet.” Japanese airmen also demolished most of the combat aircraft present on O’ahu.

By 10:00 the battle was over. Morison’s verdict: “Never in modern history was a war begun with so smashing a victory.” And yet I would cite three reasons why Pearl Harbor was a calamity for imperial Japan. First, because the Kidō Butai was so far from home port, it by necessity flouted the strategic principle of “continuity.” The military grandmaster Carl von Clausewitz urges commanders to find their enemy’s “center of gravity,” that which gives the enemy society and military forces cohesion. Once they’ve detected the center of gravity and struck an effective blow at it, they should land “blow after blow, all in the same direction” until the enemy capitulates or can no longer resist.

It’s the same principle you see in the ring, when one boxer knocks the other off balance, then pounds away repeatedly till he scores a knockout.

Military forces are an obvious center of gravity for any combatant—Clausewitz gives them pride of place—and I would agree with Imperial Japanese Navy officers that the Pacific Fleet was the center of gravity of U.S. naval power in the Pacific. Because the Japanese logistical lifeline was overstrained, though, the fleet was unable to linger off O’ahu long enough to deliver blow after blow until the fleet and its supporting infrastructure lay in smoking ruins. Nor did the Kidō Butai have enough fuel to hunt down the American carriers at sea or lay in ambush until they returned to port.

Japan landed a crushing one-two punch on December; it did not score a knockout blow, and it could not deliver a flurry of punches that added up to the same thing. Battleships were wounded or died; U.S. carrier aviation lived, even though it was a fugitive for the time being.

Which leads to the second reason Pearl Harbor was a failure for Japan. Much as Admiral Chester Nimitz did when he arrived in Hawai’i late that December to take command of the Pacific Fleet, Morison concludes that the Japanese struck the wrong targets: “They knocked out the Battle Force and decimated the striking air power present; but they neglected permanent installations at Pearl Harbor, including the repair shops which were able to do an amazingly quick job on the less severely damaged ships.” (Indeed, most of the battlewagons stricken on December 7 returned to service. They exacted vengeance from the Japanese battleship fleet late in 1944, pummeling the foe at the Battle of Surigao Strait in the Philippines—history’s last major fleet-on-fleet gun battle.) Nor did Japanese aviators strike at the power plant or fuel tank farm supplying the naval station and the fleet. Nor did they inflict as many casualties as they might. Early on a Sunday morning in port, after all, many crewmen were ashore enjoying some R&R and thus not in Japanese crosshairs.

A fleet withers on the vine without drydocks, repair facilities of all kinds, and shore services such as fuel and electricity. As Rear Admiral Bradley Fiske observed a century ago, bases in effect replenish the stored energy that fighting ships discharge while riding the waves or dueling opponents. It recharges their batteries. And as Admiral Thomas C. Hart pointed out in the wake of the Pearl Harbor raid, demolishing infrastructure would have set back the U.S. war effort in the Pacific far longer than did the assault on the battle fleet.

So Japanese battle planners chose the wrong targets for December 7. The fleet may have been the U.S. Navy’s center of gravity, but the naval station was the indispensable enabler for the fleet’s fighting endeavors. You don’t get the one without the other.

And third, think about the politics of Pearl Harbor. In the movie Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) and again in Midway (2019), the Hollywood version of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the commander-in-chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy, laments after Pearl Harbor that “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.” (The real Yamamoto didn’t use such poetic phrasing, but in his writings he did say something conveying the same meaning. Moviemakers simply made his words memorable.)

Think about what he was saying. America was slumbering in that it was reluctant to get involved in foreign wars, but it was a giant in that it boasted gargantuan natural resources and industrial capacity. In other words, it was an industrial giant with the latent capacity to make itself a military giant. And it could translate that potential into working military might given sufficient resolve. The U.S. economy was nine to ten times the size of Japan’s. You don’t want to poke a potential enemy with that vast a potential military advantage. And yet Japan did at Pearl Harbor. It mobilized the American people and society to transform latent into actual military power. Their fury aimed that juggernaut at the empire across the Pacific.

And wartime resentments burned long after the guns fell silent in 1945. My family is a military family, and was a navy family during World War II. Both of my granddads were enlisted men; one had his ship, an escort carrier, sunk out from under him. Thankfully he survived despite giving a wounded shipmate his life vest. Imagine in 1987, when I pulled up in my grandparents’ driveway in Tennessee in my first car—a fire-engine-red Honda! That was an ugly situation.

And that is the main reason Japan erred at Pearl Harbor. You do not want to pick on a musclebound adversary that might bestir itself to smite you down.

What should Japan have done instead? Almost anything else. It could have chosen better targets if it opted to go through with the attack. Maybe it could have carved out a durable sphere of supremacy in the Pacific if it bought enough time.

Or it could have stuck to its prewar game plan. Not until 1941 did Yamamoto convince military leaders to strike Pearl Harbor. The navy’s longstanding strategy, honed across decades, envisioned waiting for the U.S. Pacific Fleet to come to the Imperial Japanese Navy after an attack on the Philippine Islands, then U.S. territory. Japanese submarines and warplanes operating from and around Pacific islands would repeatedly strike the American fleet on its westward voyage, whittling it down to size until the Japanese fleet could engage and defeat it somewhere in the Western Pacific—Japan’s home turf.

That was a sound strategy.

Instead, the Japanese leadership gave in to what Morison called “strategic imbecility.” Tactical brilliance—for which the Japanese armed forces were justly acclaimed—could not make up for strategic illiteracy among the senior leadership.

And that is why Japan failed at Pearl Harbor.

Dr. James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the US Naval War College and a Nonresident Fellow at the Brute Krulak Center, Marine Corps University. He is slated to present these remarks on board the battleship Massachusetts, Fall River, Massachusetts, this December 7. The views voiced here are his alone.